Ghost of a Chance

How the residents of Silverton, Colorado beat the odds to rescue a long-abandoned mining town.

Preservation | Spring 2015

By Kate Siber

Click here to read the story on Preservation’s website

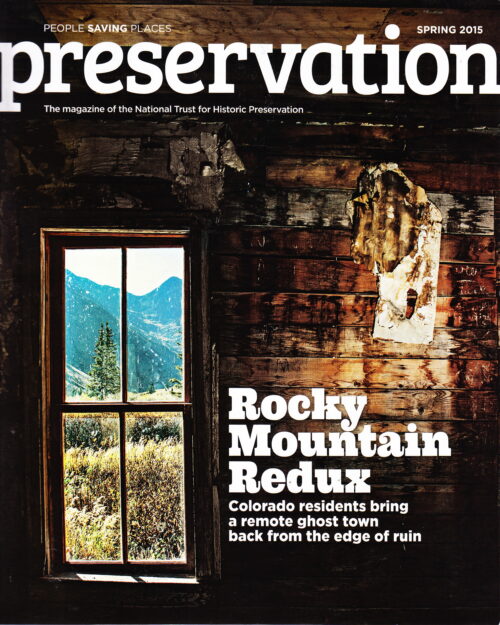

Twelve miles northeast of Silverton, Colorado, right where the spruce and fir forests thin to alpine tundra, nine abandoned wooden structures rise out of a flower-specked meadow. For more than 100 years, they have stood as emblems of their residents’ hardiness and optimism, weathering high winds, temperatures below -30, and snow deep enough to bury their eaves. On a warm summer morning, I gingerly walked inside these buildings, finding linen wallpaper and 1907 newspapers molting from the walls and ceilings. Shelves remained where they were left more than a century ago, and constant breezes moaned through the cracks in the boards. A question arose in my mind: How did the residents of this remote outpost tolerate these extreme conditions—said to be second in harshness only to Alaska—so many years ago?

This is the enduring question of Animas Forks, one of Colorado’s best remaining ghost towns and the crown jewel of the Alpine Loop, a 65-mile, four wheel-drive byway that winds through two 12,000-foot passes, spectacular peaks, and ruins from the late 1800s mining boom. First established in 1874 and incorporated in 1881, Animas Forks was a hub for hard-rock silver and gold mining. It boasted a population of about 400 before its decline in the 1910s. General stores, saloons, restaurants, boarding houses, a blacksmith, a livery, and a drugstore crowded this inhospitable slope, which is wedged among 11,000- to 14,000-foot mountains. Immigrants from as far as Eastern Europe and Scandinavia braved avalanches, fires, and the dank, dangerous conditions of the mines, but they also must have witnessed the shattering beauty of this perch, from the rainbows that emerge after thunderstorms to the crystalline silence of snowfall.

Because it is so well preserved, Animas Forks is one of the best-loved ghost towns in the state, and in recent years, its popularity threatened its preservation. Over the past decade, visitation has soared to an estimated 250,000 every year, thanks in part to improved ATVs and side-by-sides that make traveling the precipitous, rock-strewn road easier and safer. Stabilization work started in the 1970s, and major repairs shored up crumbling structures in the late 1990s, but the ravages of time still chipped away at the site. Emboldened by its deterioration, some visitors peeled away boards, broke windows, carved graffiti, and even pried the square-headed nails out of the jailhouse walls, leaving pockmarks. Meanwhile, the harsh weather contributed to sagging roofs and splintering siding. One roofline was even beginning to sway. If Animas Forks were to survive, something had to be done.

“It’s one of the most significant of the Bureau of Land Management’s (BLM) historic sites in the country, and it was deteriorating,” says David Singer, a local preservationist and founder of Silverton Restoration Consulting. “My first drive up there every spring was fraught with worry. I’d cross my fingers that nothing had collapsed.” In response, a group of dedicated local citizens, organizations, and land managers centered around Silverton, the nearest inhabited town, stepped up. They secured a listing on the National Register of Historic Places for the townsite in 2011, developed a historic structures assessment, and snagged $330,000 in grant money for an ambitious two-phase stabilization and restoration project.

Animas Forks is among the most popular of the area’s historical mining sites, but it’s just one of many that this small, devoted community has rallied to protect. Over the past few decades, the all-volunteer San Juan County Historical Society, based in Silverton, has gathered more than $12 million in grant money for preservation work. With the help of other historical societies in nearby Ouray and Hinsdale counties, local organizations, and dedicated staffers at the Forest Service and BLM, the San Juan Mountains are now home to a trove of intact, nationally significant historic sites, including boarding houses, mills, trams, and former residences. Together, they make a wild chapter in American history come alive for hundreds of thousands of visitors every year.

Silverton, a tidy grid of candy-colored Victorians rimmed by peaks, is itself a National Historic Landmark with deep mining roots. Established in 1874, it was the hub of four railroads. In the early 20th century it ballooned to 5,000 people, who built churches on one side of town and saloons and brothels on the other. Few women lived here in the early years and, with so many young men, the town was famously rowdy. But up until 1991, when the last mine closed, more than 2 million troy ounces of gold, 51 million ounces of silver, and many other minerals poured from the mountains.

Unlike other Colorado mountain towns, Silverton (population around 700) hasn’t gentrified, which is part of the reason it’s so well preserved. Some of the old miners still live here and spend afternoons constructing exhibits for the historical society’s museum. The vintage Durango & Silverton Narrow Gauge Railroad ferries visitors through the mountains, and the main drag is still dotted with grand Victorian facades. In the winter, storms dump feet of powder, and residents use kicksleds to glide around the snow-packed streets. It’s a place with few rules and a spirit of freedom and self-reliance. As a result of this ethos, Silverton didn’t even have a historic preservation ordinance until about five years ago.

“We left it to the marketplace to have such a beautiful little downtown,” says Beverly Rich, the retired county treasurer and a longtime board member of the San Juan County Historical Society. Luckily, she adds, “Silverton in general developed a real ethic about historic preservation.” It’s not only how the residents make their living, it’s who they are. Dubbed the “queen of preservation” by some locals, Rich is a slim, straight-backed woman with cropped pewter hair and a proper demeanor that belies the toughness necessary for living at 9,300 feet. She taught herself to write grants and, on her own time, has helped pull in a remarkable haul of funding. Over the years, she and the society have won awards from the National Trust, the Mining History Association, and History Colorado, but Rich’s motivations, like those of many others in town, run deeper.

“I was born and raised here and I have a deep love for mining history,” says Rich, who started working for the society at age 19. “My dad was a miner. My husband was a miner. It’s about capturing those little pieces of culture, things like how when I was growing up as a child, it was an automatic thing to raise your voice to a man, because miners were deaf.”

The Historical Society was founded more than 50 years ago, but it wasn’t until after the historic train depot was dynamited that the organization led its first restoration project. (The culprit in the 1975 incident was never caught, but the depot was rebuilt within a few months.) In 1992, another tragedy turned into an opportunity. Silverton’s 1908 town hall caught fire, and the society secured the first emergency grant from the Colorado State Historical Fund to restore it. The town of Silverton decided to act as its own contractor, buying supplies locally and hiring recently unemployed miners. Later, they won a National Preservation Honor Award from the National Trust for the project, and residents began to see that restoration work not only preserved integral parts of their culture, but also helped attract tourists and bolster the local economy.

Since then, the Historical Society, with local partners such as the Mountain Studies Institute, Silverton Restoration Consulting, and state agencies, has implemented many other preservation projects. It successfully pursued grants to repair the roof at the Miners Union Hospital, a 1908 brick-and-limestone building that now houses the Silverton Standard & the Miner, the town’s 139-year-old newspaper; the food bank; and other community organizations. Nearby, $650,000 in funding fueled a 1996 restoration of the county jail, which is home to the Historical Society’s museum and thousands of artifacts, from mining and railroad memorabilia to the original cell block that once locked up outlaws.

Locals also built a climate-controlled concrete archive that protects thousands of historic maps, photographs, letters, and diaries. (Open to the public every Thursday, it attracts authors and genealogy buffs.) And, in the mountains, the society contributed to projects such as stabilizing the 1904 Old Hundred Mine boarding house, which threatened to tumble from its cliffside perch into the valley 3,000 feet below. They also arranged an estimated $1.5 million ongoing rehabilitation of the Shenandoah-Dives Mill (colloquially known as the Mayflower), which was donated to the organization after the last mine closed.

Even with funding, preservation work here isn’t easy, and often the mines and boarding houses were built in exceedingly inconvenient places. Over the years, preservationists have enlisted the help of helicopters to drop off supplies on cliffs and mules to cart in equipment in areas where there are no roads. They’ve wrestled with the damage inflicted by marmots and huffed up hillsides in the thin mountain air. But they’ve also stumbled upon remarkable discoveries, including a 5-ounce bag of almost-pure gold dust hidden for decades at the Shenandoah-Dives Mill.

On my summer visit to Animas Forks, I traveled first over two precipitous 10,000-foot passes to Silverton and then up a bone-rattling dirt road. A delicate light streamed through the clouds, casting long shadows over the mountains. The slopes glowed electric green from the recent monsoons, and purple-tipped grasses and wildflowers bloomed by the roadside. At Animas Forks, work crews hammered nails on roofs and sawed wood. I could see the progress they had made over the past two summers: They improved drainage; graded paths; repaired porches, door jambs, and roofs; and installed new doors and shatterproof polycarbonate windows, among many other measures. Singer, whose company oversaw the project, also developed new interpretive panels for the William Duncan House—the most well-preserved structure in the town—and the jail.

“When you start working on these buildings, people see that and they tend not to vandalize it quite as much,” says Loren Lew, the leader of the construction crew and a master craftsman who has lived in Silverton for more than 40 years. “For some people, it’s just a tourist attraction, but for others, they start asking questions. That’s what we like to see—people getting invested in it. Then they do all your work for you, helping to police and maintain the area.”

It’s also easy to see what happens when these buildings aren’t restored. On the other side of the road, the hulking Columbus Mill rises out of a hillside like a spooky shipwreck. It sits on private land, and over the years, without stabilization, it has started to splinter apart into a heap of timbers. Travelers through these high alpine roads find slopes littered with the sun-bleached bones of old structures, strewn about the alpine tundra, unrecognizable from their past glory.

Lew, whose face is crinkled from years working in the high-altitude sun, has handled dozens of restoration projects and is now teaching the next generation of carpenters how to look at construction through the unique lens of preservation—and to solve the problems endemic to the high country. (The morning I visited, Lew arrived to find the shingles he’d mounted the day before gnawed by a porcupine.)

There is still plenty of preservation work needed in the San Juan Mountains, especially as funding for land agencies declines. (Between 2010 and 2017, the Forest Service’s local heritage program budget is slated to shrink by 50 percent.) Just over the hill from Animas Forks, for example, is the towering ruin of the Sound Democrat Mill. Inside, giant rusted wheels sit idly where they ground to a halt more than 100 years ago. The old Wilfley shaking tables, where crushed ore was shaken to separate the heavy minerals from the lighter ones, are frozen in place or have collapsed. Wheels, springs, bolts, cables, and scraps of canvas litter the site. Even the old ore-crushing stamps, with the original embossing, are still there. Stabilization in the early 1990s prevented the Sound Democrat from collapsing, and this winter the same group that saved Animas Forks was approved for a grant that will cover more structural work and rehabilitation for the mill.

A few weeks after my initial visit, on a bright Friday morning shifting with clouds, I returned to Animas Forks. The flocks of tourists had disappeared, but another crowd started to gather. Announcements in the local papers invited the public to a celebration of the stabilization work, and about 50 people showed up, from land managers and preservationists to artists, hotel owners, the town electrician, and even Ernie Kuhlman, an old miner with suspenders, a thinning white pompadour, and a horseshoe mustache who has been visiting the site for half a century.

That morning, speeches were made and awards bestowed. Nearby, marmots squeaked, the last of the wildflowers clung to life, and bleach-white clouds hung so low, they seemed to bring the ghostly town closer to the sky. With the buildings standing strong, it felt as if Animas Forks were still very much alive. And this event, I realized, probably wasn’t unlike gatherings that took place here more than 100 years ago—like-minded people, all tied to the mountains, united by a common cause.