Mississippi Reckoning

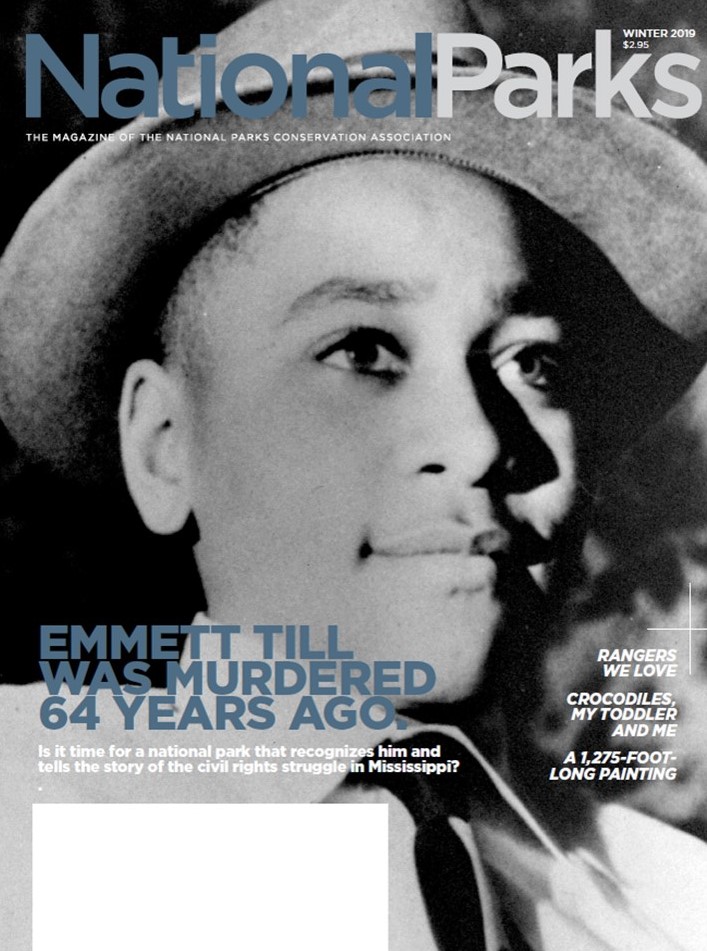

Emmett Till was murdered 64 years ago. Is it time for a national park that recognizes him and tells the story of the civil rights struggle in Mississippi?

National Parks | Winter 2019

By Kate Siber

When 14-year-old Emmett Till left Chicago for Mississippi on a southbound train in the summer of 1955, he almost forgot to kiss his mother goodbye. The bright-eyed youth was excited for a big trip to visit his great-uncle, Mose Wright, a sharecropper and preacher who lived in a small home near Money, a Mississippi Delta whistle stop.

Till was a confident, fun-loving kid, quick to play pranks and joke around. He loved baseball and had a soft spot for animals. His mother, Mamie Till Bradley, knew he was unaware of the Jim Crow mores of the South and how dangerous it could be there for African American children like him. Before he left, she tried to impress upon him that Mississippi was different. “Even though you think you’re perfectly within your right, for goodness sake take low,” she said, according to subsequently published accounts. “If necessary, get on your knees and beg apologies.”

It took all day to travel 650 miles to Mississippi, and Till was flowing over with excitement, barely able to sit still. In the great alluvial plain of the Delta, agricultural fields stretched as far as Till could see, punctuated by small copses and the occasional rural settlement. In the depths of August, stifling heat hung heavily over the land, some of the most fertile in the world.

With his cousins, Till fished and swam and horsed around. Then one evening, they went to a local store, Bryant’s Grocery, and just before leaving, Till allegedly whistled at the 21-year-old white proprietor, Carolyn Bryant, breaking one of the South’s most notorious taboos.

A few days later, Till was sleeping when the men came for him. In the predawn darkness, the family could see the gun in the beam of the white men’s flashlight. Wright and his wife, Elizabeth, begged them not to take their nephew. But the men ordered the boy to get dressed, led him out of the house and into a vehicle, possibly a truck, and drove west on gravel roads with the headlights off. Several days later, a fisherman found Till’s body, grossly disfigured from torture, in the Tallahatchie River. Someone had tied a 70-pound cotton gin fan to his neck, hoping he would never be seen again.

But unlike so many African Americans in Mississippi who were murdered, Emmett Till was not forgotten. Till Bradley had his body shipped north for the funeral and then demanded that the casket remain open during the viewing and service so the world could see what white racists had done to her son. Jet magazine subsequently published photographs of Till’s mangled corpse accompanied by his devastated mother, laying bare the racial realities of the Jim Crow South. Till’s murder sparked international outrage and, according to many scholars, helped catalyze the modern civil rights movement. When she refused to give up her seat on the bus, Rosa Parks said she had Till on her mind.

Today, two markers along an isolated dirt road memorialize the site where Till’s body was dragged from the water, but they keep getting shot up and replaced. On an August morning, I pulled over with my tour guide for the day, Jessie Jaynes-Diming, owner of Mississippi Delta Experience Touring. We walked through a clearing to the weed-choked banks of the river. Cicadas buzzed in the heavy morning heat, and dragonflies looped around. It wasn’t hard to imagine how people could disappear here in the murky water. Back at the road, I read the memorial signs, perforated with bullet holes. Someone had stuffed a rose into one of the pockmarks. Jaynes-Diming and I stood there in silence.

“It’s disappointing in a way but enlightening also,” she said finally. “I don’t want to get too comfortable and not know that’s the way people think. If that’s the way they feel about it, leave it like that.”

Jaynes-Diming and I had met in Sumner that morning, in front of the courthouse where an all-white, all-male jury let Till’s killers go free. (They later confessed in a magazine interview.) Over the course of several hours, we visited some of the key landmarks connected to this notorious crime, which still occasionally resurfaces in the news. (In 2018, the Department of Justice informed Congress it had reopened the case because of newly discovered information, which has not yet been disclosed.)

The National Park Service is mandated to preserve the natural and cultural heritage of America, but currently, there are no sites in the system that protect places connected to Emmett Till — or any of Mississippi’s complicated civil rights history. That might change soon. In 2017, Congress passed legislation requiring the Park Service to undertake a study of civil rights landmarks in Mississippi. The three-year process could eventually lead to the creation of a new national park site — or several — in the state.

But with such a rich history of both courageous activism and devastating violence, which stories will be commemorated? And who gets to tell them? I traveled to Mississippi to see some of the places under consideration and to learn about local concerns and hopes for how this history will be memorialized. Over the course of several hot August days, starting in Jackson, I drove a loop north and clockwise through the Mississippi Delta, where some of the most significant events in the civil rights movement took place.

Among other sites, I visited Bryant’s Grocery, the Sumner courthouse and the Jackson home of Medgar Evers, the civil rights activist assassinated in his driveway in 1963. The legislation calling for what is known as a “special resource study” specifically identifies these places as well as the Neshoba County jail where voting-rights activists James Earl Chaney, Andrew Goodman and Michael Schwerner were held before they were ambushed and murdered in 1964, and the office of Gilbert Mason Sr. in Biloxi. Mason helped organize wade-ins to desegregate beaches in the city. Many locals have their own views on which figures, stories and places they believe the Park Service should recognize. In 2018, 350 people showed up at six statewide public meetings to make their recommendations.

Some of these sites might become federally protected in other ways. The U.S. House of Representatives passed a bill in May that would designate the Medgar Evers House, currently a museum, as a national monument; the Senate could vote on it soon. In 2017, in the same memorandum in which Secretary of the Interior Ryan Zinke recommended shrinking national monuments such as Bears Ears and Grand Staircase-Escalante, he also proposed three new ones, including the Medgar Evers House. President Donald Trump could designate it under the Antiquities Act.

“The stories of Medgar Evers and Emmett Till are very important chapters in both Mississippi and U.S. history,” said Alan Spears, cultural resources director at NPCA. “Our hope is that we can commemorate their legacies without tying such an administrative action to a rollback of existing national monuments.”

Though some Mississippians would prefer to sweep the state’s disturbing civil rights history from view, that resistance has lessened over time, and there is widespread support for new park sites in the state, whether they are established through the Park Service study or other avenues. “I think there’s a hunger for people, black and white, to know the story — in Mississippi and everywhere,” said Jerry Mitchell, the journalist whose investigative reporting at The Clarion-Ledger in Jackson helped bring some of Mississippi’s most notorious Klansmen to justice, including Medgar Evers’ killer.

The Mississippi Civil Rights Museum is a tangible reflection of the cultural shift toward openness over the last two decades, and though it’s not part of the Park Service study, several people recommended I start my journey there. Opened in late 2017 in a slick, contemporary building in downtown Jackson, the museum unflinchingly tells the story of racial subjugation from the time of slavery to the present day. Artifacts include shackles, antique posters breezily advertising slave sales, the gun that killed Medgar Evers and the magazine that published photos of Emmett Till’s corpse.

During the slavery era, Mississippi was known as a particularly violent state, perhaps because of the sheer effort required to tame this fertile, forested, swampy land and the incredible wealth at stake. After the Civil War, slavery ended in name, but the system of violent subordination remained. One of the most gut-wrenching displays in the museum is a glowing list of names of the people lynched in the state. According to a placard, between 1877 and 1950, Mississippi mobs murdered 600 people, many of whom were tormented in carnival-like affairs that white families, including young children, attended. No other state can claim as brutal a history of lynching.

The extrajudicial violence that enforced racial oppression continued in different forms as the civil rights movement gained steam. Just north of downtown Jackson, Medgar Evers’ trim turquoise home sits on a serene, leafy street. Evers was serving as the first field secretary for the Mississippi NAACP when a white supremacist shot him in his driveway with a high-powered rifle one evening in 1963. His wife and children heard the gunfire from inside the house. No ambulance ever came for him, and when he was taken to the nearest hospital, the staff almost didn’t treat him because of the color of his skin. Evers died within 40 minutes of arriving.

Now a museum operated by Tougaloo College, the house is open by appointment. Minnie White Watson, the sole staff member, was a freshman in college when she first met Medgar Evers, whom she described as gentle and hardworking. Hearing him speak opened her eyes to the civil rights struggle, and she worked with him briefly. Now she gives tours of the home and tells his story — but she doesn’t much like talking about her own involvement. “I get emotional,” she said.

Evers, a World War II veteran, saw and experienced injustice and violence throughout his life. As a kid, he knew that a black boy who had dared to venture to the whites-only fair in his town had been lynched. While working as an insurance salesman as a young man, he had witnessed the deep poverty of people who still lived in dirt-floor houses in plantation-style servitude, and that helped shape him into an activist. He went on to organize voter registration drives and boycotts in the 1950s and ’60s and investigated Emmett Till’s murder for the NAACP. The Evers’ house received numerous threats, from menacing phone calls to a Molotov cocktail.

“We would ask questions of Medgar — ‘Why are you doing it?’” Watson said. “He said it was on his shoulders. Somebody has to do it.” Evers knew that he lived with a target on his back, she said, but he was committed to the cause. His conviction inspired others.

“You looked at it, and you said, ‘He’s right. When somebody tells you where you can live, where you can sleep, where you can eat, where you can worship, even where you can relieve yourself, you are not yourself,’” she said. “You don’t own anything when somebody can tell you all of that. So it hits you: What do I have to lose? Nothing but my life — and it ain’t mine anyway.”

Later that morning, I traveled about two hours north to Cleveland, Mississippi, to meet Rolando Herts, the director of the Delta Center for Culture and Learning. The center oversees the Mississippi Delta National Heritage Area, a region including civil rights and blues music landmarks that the Park Service has recognized for its unique cultural value. The Delta Center and the heritage area hosted the first public meeting for the Park Service. Echoing comments gathered from Delta residents, Herts said he is concerned that the Park Service will choose to memorialize only one or two sites related to Medgar Evers and Emmett Till.

“There’s so much more to the civil rights story,” Herts said. “Community members recognize that and are very vocal about that. There are all these other stories of important figures who contributed greatly to the civil rights movement in the Delta. It would be a shame not to tag those on to this broader story of civil rights in the state.”

Herts invited several other locals to our meeting, and to our surprise, about 15 people showed up. He ordered fried chicken, chips and soda for all, and we gathered in a circle so everyone could share their opinions and stories. Many in the group want the Park Service to highlight the collective nature of the movement and not focus only on famous leaders — typically men — or murders and other atrocities. They also hope to showcase stories of hope and resilience. Herts is advocating for the Park Service to create a civil rights trail that could boost tourism in the depressed region. In 2011, the Mississippi department of tourism created the Mississippi Freedom Trail to commemorate people and places that played a significant role in the civil rights movement, but Herts and others picture an expansion of the concept that, with Park Service support, could include trained guides and visitor centers.

One of the men, Charles McLaurin, a member of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee in the 1960s, spoke about the renowned activist Fannie Lou Hamer. The youngest of 20 children in a sharecropping family, Hamer worked in the cotton fields from the age of 6. She was fired from the plantation she grew up on for trying to register to vote. The injustice she suffered inspired her to co-found the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party, run for Congress and deliver a landmark nationally televised speech at the Democratic National Convention in 1964.

“I think they should look at the spirit of this woman, the respect, the courage, the determination,” said McLaurin, who worked alongside Hamer registering voters and later acted as her campaign manager. He helped establish a garden and statue in Hamer’s honor in Ruleville and would like to see it recognized.

Willena White shared the story of her father, Ed Scott, the first nonwhite catfish farmer in the country, who battled prejudicial lending practices and discrimination by managers of local plants, who refused to process his fish. The family is developing the Delta Farmers Museum and Cultural Learning Center, which they would like to become a park site.

Myrna Smith-Thompson, executive director of the Knights and Daughters of Tabor, a civic organization, came to the meeting to call attention to Mound Bayou, a town founded by former slaves that thrived in the early 20th century and acted as a refuge for African Americans throughout the region.

“A lot of the good things that were done don’t get the attention like an injustice or a murder,” said Smith-Thompson. “There were some other things that were accomplished by African Americans, and the stories of the strategies, the visions, the creativity, the things that they did to assure the growth and sustainability — the mere survival — of African American people … those are the things I’d like to promote.”

Other concerns loom large among the Mississippi residents I spoke with about the possible creation of a new park site. From all communities, there is a deep distrust of the federal government. In addition, many people expressed how important it is that these stories be told from the perspective of those who lived them.

“What you hear today on the civil rights story is what other folks told,” said Darryl Johnson, a preacher and the mayor of Mound Bayou. “We don’t tell it ’cause we’re still goin’ through it — we are still having a civil rights problem. When other folks tell our story, I get frustrated. All of us do. They’ll take it, just like the white man did, and say, ‘I got it, I’m gonna show you how to do it,’ and we’re still left out. The bottom line is we need to tell our own stories.”

Ben West, the chief of planning who is overseeing the study, is keenly aware of the stakes of the project, one of the biggest studies the Park Service’s Southeast Regional Office has ever led.

“The perspective I got firsthand in Mississippi was a) how personal this is to so many people, and b) a deep concern,” he said. “People are saying, ‘Hey, Park Service, you better get this right. You better address the concerns and resources of the movement.’” West is enlisting the help of local civil rights scholars and historians to consult on the project. Alan Spears of NPCA is also organizing meetings to help locals come to a consensus about which sites to recognize.

Sumner is one of the communities participating in the process. A rural Delta town, it looks as if it could be the set for a 1950s film. The stately brick Tallahatchie County Courthouse sits in the center of the town square, which is framed by small-town businesses — a lawyer’s office, beauty salon, drugstore, restaurant. Outside the courthouse, a Confederate monument still stands, and the interior of the courtroom looks precisely as it did in 1955 when a jury acquitted Emmett Till’s killers. For more than 50 years, many people tried to forget the murder, but it only grew in significance.

In 2006, Jerome Little, the first African American president of the Tallahatchie County Board of Supervisors, organized a multiracial commission to help the town come to terms with the killing and begin to heal. In 2007, the commission offered a formal public apology to the Till family. Over the following years, the group also restored the courthouse and established a museum, the Emmett Till Interpretive Center, across the street. I had booked a tour of the museum and the courthouse with Patrick Weems, co-founder and director of the center. As we walked through the courtroom with its simple white walls and wooden chairs, Weems said that Little, who died in 2011, dreamed that one day the Park Service would assume management of these landmarks.

“It would be surreal for this community for the Park Service to preserve this story,” Weems said. “In 1955, the federal government turned its back on Till and the Till family — they did not pursue any kind of FBI investigation. For the federal government to take over, I think it continues this process of restorative justice. There’s a symbolic nature to it.”

The reconciliation commission helped the community face the murder and its aftermath, but racism still threads through life here, usually emerging in more subtle forms, such as the continued silence of many white people. One example is Bryant’s Grocery. During my tour, Jaynes-Diming and I pulled over to the side of the road in Money, little more than a set of train tracks, a cotton gin and a few homes. I didn’t notice Bryant’s Grocery at first. The old wooden porch has fallen into a heap, and vines have overcome the crumbling brick walls. The family that owns it — the children of an unrepentant juror, Ray Tribble — have not maintained it and instead let it decay. Over the years, more than a half-dozen people have attempted to purchase the store to restore it, but the family has refused the offers. They are currently asking $4 million for the property. (The family did not respond to a request for comment.) Despite the deterioration of the store, visitors still come by regularly to see it.

The family did secure a state historic-preservation grant earmarked for civil rights-related projects to restore the service station next door and create a small visitor stop. The day we drove there, it was quiet, sparkling white in the hot sun. “I’ve never seen it open,” said Jaynes-Diming as we peered inside the plate-glass windows. Inside, quaint 1950s memorabilia crowded the floors and shelves, but there’s no mention of Till anywhere — or of the racial injustice that defined that era. “I’ve tried to get it open,” said Jaynes-Diming, “but always no response.”

Part of the difficulty and urgency of remembering civil rights history now is that many people, like Darryl Johnson of Mound Bayou, feel that the concerns of that movement are still painfully relevant. An African American college student I met in Clarksdale, Mississippi, told me about the fear she experienced when she began to hear racist talk on campus following President Trump’s election. Another African American woman in her 20s, who attended the meeting in Cleveland but didn’t want her name used, said that she didn’t think the state, or the country, has come all that far in terms of race relations.

“The fight has been a courageous fight, but unfortunately … there’s still no protection for people reaching for freedom,” she said. “How is it that we are told we are in a free space, we’ve progressed, when we’re really in very similar bondage to our ancestors?”

For our last stop on the tour, Jaynes-Diming and I visited the barn where Till was killed for acting free. Just off a remote road full of heaves and cracks and down a long driveway, the barn sits next to a farmhouse on top of a hill overlooking a primeval cypress swamp and soybean fields. The dentist who owns the property allows people to visit it and even enlarged the driveway so buses can turn around. The barn is tidy and well-kept, and the peaceful beauty of the rural backdrop is unsettling in light of the horror that unfolded here more than a half-century ago, when grown men tortured an eighth-grader thinking — knowing — that the world they lived in would let them get away with it. It is a poignant place to contemplate the complex legacy of Emmett Till, but there isn’t any sign, marker or formal indication of the site’s significance in American history. Right now, it’s just a barn on a lonely road in rural America.