On Utah’s Cedar Mesa, Solitude and the Thrill of Discovery

The Washington Post | April 18, 2013

By Kate Siber

Well after nightfall on a recent Friday, I steered my sedan through a barren patch of desert in southeastern Utah. Outside the windows, juniper, piñon and sage jerked in the wind. No headlights lit the road except for my tenuous beams, a feeble match for the sea of darkness.

I’d just inched up a mess of nerve-fraying switchbacks on Highway 261, where I’d peered past an unguarded edge into a vertiginous gulf of night below. Now the frozen mud ruts of a county road scraped the bottom of my car, and quite honestly, I didn’t know precisely where I was. At that moment, I questioned the wisdom of my weekend mission: camping and finding ruins on Utah’s Cedar Mesa. It was 11 p.m., about 20 degrees and very windy — hardly ideal weather for camping.

“Do you want to just pull over soon and set up our tents?” asked Amanda, one of my two travel companions. I veered left onto a small, flat spot and she bounded out of the car, disappearing into the darkness. A few moments later, she returned, arms beckoning.

“It’s perfect!” she called.

It was. Despite the howling cold, the sky was clear and stars spilled across it, competing in grandeur only with the rising moon, the shape of a peach stone. Amanda, Ryan and I set up our tents in the flat sand, and before drifting off, I watched the moon cast juniper shadows on the surface of the tent, turning the dome into a glowing web of branches.

Bluff, Cedar Mesa is a riddle of canyons, moss-draped oases and sandstone spires. Despite the area’s desolate beauty, travelers routinely overlook it in favor of better-known national park sites such as Canyonlands, Arches, Mesa Verde and Chaco. They’re missing out.

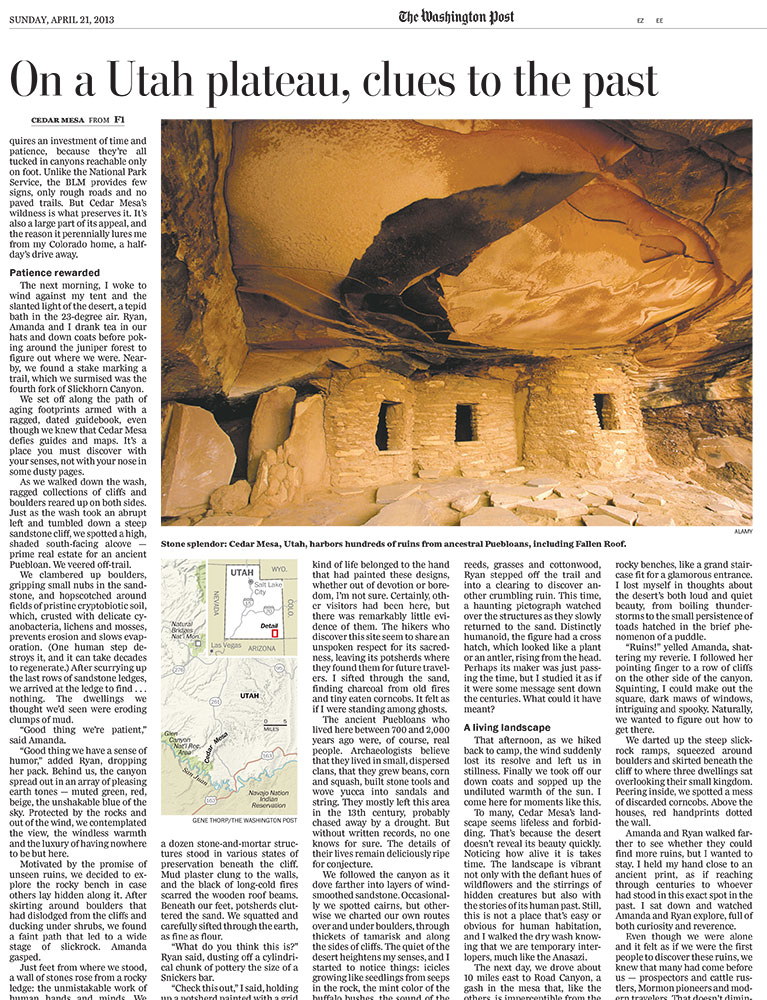

Cedar Mesa, which is on land administered by the Bureau of Land Management, harbors an array of colorful geological formations and hundreds of ruins from ancestral Puebloans, also commonly called the Anasazi, or “ancient enemy” in Navajo. Many sites have never been excavated, named or mapped, and few modern eyes have seen them. Although ruins in national parks can be larger and more elaborate, Cedar Mesa offers a rare slice of solitude and the thrill of discovery.

Discovering these ruins, however, requires an investment of time and patience, because they’re all tucked in canyons reachable only on foot. Unlike the National Park Service, the BLM provides few signs, only rough roads and no paved trails. But Cedar Mesa’s wildness is what preserves it. It’s also a large part of its appeal, and the reason it perennially lures me from my Colorado home, a half-day’s drive away.

Patience rewarded

The next morning, I woke to wind against my tent and the slanted light of the desert, a tepid bath in the 23-degree air. Ryan, Amanda and I drank tea in our hats and down coats before poking around the juniper forest to figure out where we were. Nearby, we found a stake marking a trail, which we surmised was the fourth fork of Slickhorn Canyon.

We set off along the path of aging footprints armed with a ragged, dated guidebook, even though we knew that Cedar Mesa defies guides and maps. It’s a place you must discover with your senses, not with your nose in some dusty pages.

As we walked down the wash, ragged collections of cliffs and boulders reared up on both sides. Just as the wash took an abrupt left and tumbled down a steep sandstone cliff, we spotted a high, shaded south-facing alcove — prime real estate for an ancient Puebloan. We veered off-trail.

We clambered up boulders, gripping small nubs in the sandstone, and hopscotched around fields of pristine cryptobiotic soil, which, crusted with delicate cyanobacteria, lichens and mosses, prevents erosion and slows evaporation. (One human step destroys it, and it can take decades to regenerate.) After scurrying up the last rows of sandstone ledges, we arrived at the ledge to find . . . nothing. The dwellings we thought we’d seen were eroding clumps of mud.

“Good thing we’re patient,” said Amanda.

“Good thing we have a sense of humor,” added Ryan, dropping her pack. Behind us, the canyon spread out in an array of pleasing earth tones — muted green, red, beige, the unshakable blue of the sky. Protected by the rocks and out of the wind, we contemplated the view, the windless warmth and the luxury of having nowhere to be but here.

Motivated by the promise of unseen ruins, we decided to explore the rocky bench in case others lay hidden along it. After skirting around boulders that had dislodged from the cliffs and ducking under shrubs, we found a faint path that led to a wide stage of slickrock. Amanda gasped.Just feet from where we stood, a wall of stones rose from a rocky ledge: the unmistakable work of human hands and minds. We approached slowly, so as not to disturb the animals — or perhaps the spirits — that lived there. Half a dozen stone-and-mortar structures stood in various states of preservation beneath the cliff. Mud plaster clung to the walls, and the black of long-cold fires scarred the wooden roof beams. Beneath our feet, potsherds cluttered the sand. We squatted and carefully sifted through the earth, as fine as flour.

“What do you think this is?” Ryan said, dusting off a cylindrical chunk of pottery the size of a Snickers bar.

“Check this out,” I said, holding up a potsherd painted with a grid and stripes. We were like enthralled children, intent on our discoveries. I wondered what kind of life belonged to the hand that had painted these designs, whether out of devotion or boredom, I’m not sure. Certainly, other visitors had been here, but there was remarkably little evidence of them. The hikers who discover this site seem to share an unspoken respect for its sacredness, leaving its potsherds where they found them for future travelers. I sifted through the sand, finding charcoal from old fires and tiny eaten corncobs. It felt as if I were standing among ghosts.

The ancient Puebloans who lived here between 700 and 2,000 years ago were, of course, real people. Archaeologists believe that they lived in small, dispersed clans, that they grew beans, corn and squash, built stone tools and wove yucca into sandals and string. They mostly left this area in the 13th century, probably chased away by a drought. But without written records, no one knows for sure. The details of their lives remain deliciously ripe for conjecture.

We followed the canyon as it dove farther into layers of wind-smoothed sandstone. Occasionally we spotted cairns, but otherwise we charted our own routes over and under boulders, through thickets of tamarisk and along the sides of cliffs. The quiet of the desert heightens my senses, and I started to notice things: icicles growing like seedlings from seeps in the rock, the mint color of the buffalo bushes, the sound of the wind scouring slickrock, and the tracks of mice and lizards.

A few miles later, in a swath of reeds, grasses and cottonwood, Ryan stepped off the trail and into a clearing to discover another crumbling ruin. This time, a haunting pictograph watched over the structures as they slowly returned to the sand. Distinctly humanoid, the figure had a cross hatch, which looked like a plant or an antler, rising from the head. Perhaps its maker was just passing the time, but I studied it as if it were some message sent down the centuries. What could it have meant?

A living landscape

That afternoon, as we hiked back to camp, the wind suddenly lost its resolve and left us in stillness. Finally we took off our down coats and sopped up the undiluted warmth of the sun. I come here for moments like this.

To many, Cedar Mesa’s landscape seems lifeless and forbidding. That’s because the desert doesn’t reveal its beauty quickly. Noticing how alive it is takes time. The landscape is vibrant not only with the defiant hues of wildflowers and the stirrings of hidden creatures but also with the stories of its human past. Still, this is not a place that’s easy or obvious for human habitation, and I walked the dry wash knowing that we are temporary interlopers, much like the Anasazi.

The next day, we drove about 10 miles east to Road Canyon, a gash in the mesa that, like the others, is imperceptible from the road. You have to find it on foot. We wound through piñon and juniper forest and descended rocky benches, like a grand staircase fit for a glamorous entrance. I lost myself in thoughts about the desert’s both loud and quiet beauty, from boiling thunderstorms to the small persistence of toads hatched in the brief phenomenon of a puddle.

“Ruins!” yelled Amanda, shattering my reverie. I followed her pointing finger to a row of cliffs on the other side of the canyon. Squinting, I could make out the square, dark maws of windows, intriguing and spooky. Naturally, we wanted to figure out how to get there.

We darted up the steep slickrock ramps, squeezed around boulders and skirted beneath the cliff to where three dwellings sat overlooking their small kingdom. Peering inside, we spotted a mess of discarded corncobs. Above the houses, red handprints dotted the wall.

Amanda and Ryan walked farther to see whether they could find more ruins, but I wanted to stay. I held my hand close to an ancient print, as if reaching through centuries to whoever had stood in this exact spot in the past. I sat down and watched Amanda and Ryan explore, full of both curiosity and reverence.

Even though we were alone and it felt as if we were the first people to discover these ruins, we knew that many had come before us — prospectors and cattle rustlers, Mormon pioneers and modern travelers. That doesn’t diminish the power of the mysteries that still live here.

Even with frequent trips, I know that I’ve uncovered only a minuscule part of Cedar Mesa. But the more unsolvable questions I find, the more they tug at me to return.